It’s almost Christmas time and in the ballet world that can only mean one thing: The Nutcracker is here. Next to Swan Lake, The Nutcracker might be one of the best-known ballet pieces in ballet and beyond. All the big ballet companies perform their own version and for all it’s an elaborate production. Whether we turn our heads to Sankt-Petersburg to the Mariinsky, to the Royal Ballet in London or to the New York City Ballet in the states, they all are putting on their own Nutcracker just in time for Christmas. For many of those companies, The Nutcracker is the most important production of the year: its earnings finance the majority of the rest of the company’s season. But while The Nutcracker might be iconic, it is no less problematic.

The concept of orientalism dates back to the American-Palestinian author Edward Said, who classifies the ahistoric depiction of “the orient” to uphold the colonial distinction between the “orient” and the “west” through the process of othering and exoticizing as orientalism. “The Orient” is a European-colonial idea that has shaped our thought process towards the very wide-spread idea of “the orient” which usually includes North-Africa, West-Asia all the way to East-Asia, like China. [1]

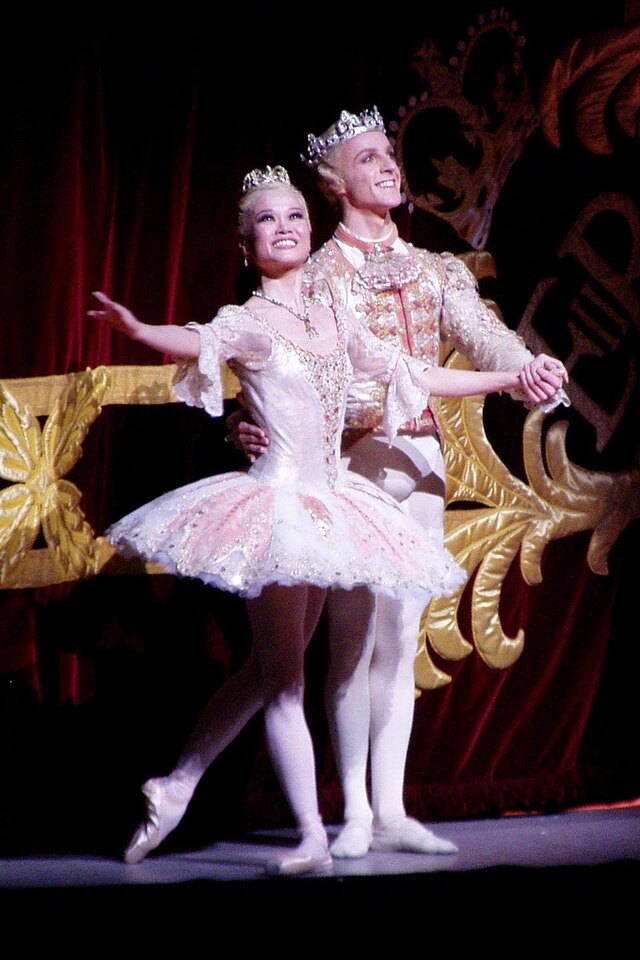

The Nutcracker is set in Germany in the late 18th century. In the first act we accompany the Silberhausens celebration of Christmas eve, where the main-character Clara is gifted the infamous nutcracker and immediately falls in love with her present. When the nutcracker appears as a real-life prince, he takes Clara on a magical journey through an enchanted forest and leads her to the kingdom of sweets: Here they encounter not only the Sugar-Plum fairy, but also the “Arabian coffee princess” and the playful “Chinese tea”. [2] Two of the scenes that are being critically discussed in the ballet world and which we can certainly describe as oriental.

So, what exactly makes The Nutcracker oriental? Historically the people involved in the creation of The Nutcracker had not been anywhere that could even remotely be considered “the orient”. Both the depiction of the Arabic world as well as China was completely based of imagination and stories, which in the late 18th century were shaped by the colonialization of the regions and the colonial ideas to support the hierarchy upholding colonialism. This has resulted in the stereotypical, falsified and racist depiction of the middle-east and China in The Nutcracker. [3]

While each interpretation of The Nutcracker showcases its own version of orientalism, they all share Tchaikovsky’s music. The Arabian dance from The Nutcracker suite rounds of the oriental stage setting, costuming and dancing as can be seen in the productions of all the big companies. The visuals range from slightly erotic depictions of the east wearing “harem pants” and showing of the dancers’ bare midriffs, to Hindu or Indian inspired costuming or just a mix from all of the above, depending on the company’s geographical location and own traditions. The jingle in the music underlines the oriental ideas behind this specific part of the show. [4]

But some companies have started to introduce changes to one of their most iconic pieces. The Scottish National Ballet has made significant changes to The Nutcracker, removing or reimaging the Arabian Coffee princess and Chinese tea. These changes are results of efforts by the company to remove racist and caricaturised depiction of the West Asia, North Africa, India and China. [5] And they are not the only one, the New York City Ballet has worked with Phil Chan, who has introduced the project “Final bow for Yellowface” to the ballet and performance world. He has introduced ways to diversify and reflect upon the ballet industry today, its whiteness, eurocentrism and its orientalism. [6]

Today The Nutcracker remains a vital part of ballet repertoires around the world – beloved, festive and financially important for ballet companies globally. Yet, beneath it’s pretty surface lies a continuation of eurocentric and orientalist ideas. The challenge facing today’s ballet world is not to abandon tradition, but to critically engage with it. By reimagining outdated portrayals and embracing cultural sensitivity, companies can preserve the beauty of Tchaikovsky’s classic while ensuring it reflects the diversity and awareness of modern audiences. In doing so, The Nutcracker can continue to enchant — not as a relic of the past, but as a work evolving with its time.