About Ice Cores Part I

A transforming icy library slowly descending towards the valley. Glacier in the northeast of Greenland. Photo: Jan Rohde

On earth there is a lot of ice and snow and not only in winter – at least at the moment. At the poles there are huge sheets of ice and in between exist many smaller and larger glaciers on high mountains. Stories are preserved in the ice. Stories from long ago. How this happened and how these stories can be brought to the surface, we will learn in this article.

This is the first of three articles of the series “About Ice Cores”. Have fun!

The Story of Giant Libraries Made of Ice

The Story of Giant Libraries Made of Ice

The glaciers and ice sheets of the earth consist of ice and snow. So far, so good. Their surface, usually white and glistening in the sun, lies picturesquely nestled between majestic mountain tops or it is so huge that far and wide only snow can be seen. Beautiful, but also exciting? Actually, it is incredibly exciting! Beneath the snow an immense treasure is slumbering. Glaciers and ice sheets are unimaginably large libraries. They store valuable knowledge about the past. The books in these libraries are not made of paper, but of ice. They are called ice cores.

Ice cores are historical books that lie dormant in the frozen libraries, waiting to tell us their story and thus something about the history of the Earth. The stories of the ice cores are written continuosly. Until the very end, until the day they are drilled. Nature learned how to write long before humans did. In fact, it learned writing long before humans even existed. Not all writings have been preserved, but some ice core books go back into the past incredibly far. That means they’ve been waiting a long time for someone to decipher their language and understand what they’re trying to tell us. We humans have been on their trail and are beginning to learn their language.

How does this language work? And how can we read it? That is what we will learn in the second article. First we have to address the question: How do we get a book from these huge libraries? Are there ice librarians we can just ask?

The Search for the Book

The Search for the Book

No, it’s probably not that simple. Ice librarians have not been discovered, yet. We have to take it into our own hands and how do we do that? We use a scientific method. Does that mean we leaf through other books, i.e. paper books or digital books, and think and ponder and come up with theories? No, we use a drill! Of course, we don’t take a drill that bores holes in walls.

Stacked ice cores. Illustration: Hanna Knahl

We won’t get far with that. The ice would only come up in small pieces and remain in a completely chaotic pile on the surface, just like the dust that trickles out of the wall. That’s not how it works! After all, we don’t take paper books off the shelf with a shredder. We want to get the ice out of the ice sheet in one piece. We want to drill an ice core and bring it to the surface. Well, we have to admit, we can’t bring the core up completely in one piece, because in some places we can drill several KILO meters deep into the ice. So we get single pieces of the core out of the ice, we get one chapter after the other from the library. But, of course, the chapters must not get mixed up. So we always have to keep the overview. This is actually not so easy, unfortunately it happens sometimes that parts of an ice core get lost on the way. That is annoying, because this means some chapters of the book are missing.

So, how do we get to the entrance of the ice library? By airplane! A small machine with runners under the fuselage instead of wheels. Because our landing strip is the ice surface. The entrance portal is supposed to be huge, but we don’t see it. We only see white, white as far as the eye can see.

Ice sheet beneath a blue sky. Photo: Sepp Kipfstuhl

So, there is no portal. Or is it? The glistening white looks so promising… because it IS the portal. The snow on the surface hides the vast library of ice BENEATH it.

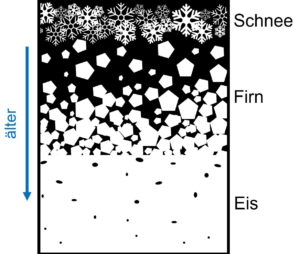

Schematic drawing of the transitions from snow to firn and from firn to ice. Illustration: Hanna Knahl

So come on, let’s go through the portal made of snow! Well, in this case that means shovelling the snow aside. Under the snow comes the firn, a layer where the snow has already become more icy and coarse-grained. This snow has been here for at least a year. The deeper we get, the more densely the snow or firn is packed. Until, finally, the increasingly dense ice appears underneath. This once was snow and then firn and now ice. It has been here for a few years now and is pressed together very tightly. With the solid piece of ice, our first chapter emerges, although it actually is the last chapter of our frozen book, because the ice up here is the youngest. The ice underneath gets older and older the deeper we drill.

Here, you can find out how an ice core is drilled and how much effort it takes:

The Drilling Camp

The Drilling Camp

Scientists such as those at the Marum at the University of Bremen or the Alfred-Wegener-Institute in Bremerhaven, as well as many others, travel to icy regions such as Greenland, Antarctica or to glaciers on high mountains and drill ice cores there.

The drilling tunnel. The drill is just above the surface. In a moment it will be lowered down hanging at a long cable. Photo: Sepp Kipfstuhl

A professional camp is necessary if a long ice core of several kilometres in length is to be drilled. Such a drilling usually takes several years. In the polar regions, drilling can only be done in summer, because in winter it is dark there all day and the low temperatures are far below freezing. In addition, violent winter storms would make the work very uncomfortable and dangerous. In winter, it must therefore be possible to barricade the borehole to make it weatherproof. To be able to leave everything as it was and not have to rebuild everything the next year, drills, laboratories and the camp are simply built into the ice. Deep trenches are dug for this purpose. These are then closed from above so that it can’t snow into them.

The drill bores vertically downwards. There are two different drilling methods, mechanical and thermal.

The mechanical method works a bit like cookie cutting. The sharp end of the drill in the shape of a cylinder pierces the ice and slowly drills its way down around the drill core, rotating.

For the thermal method, the ice cream parlour trick is used. Ice-cream sellers use a hot spoon to form particularly beautiful chocolate ice-cream balls. Thermal drilling works in a similar way. Heat is used to melt a ring around the ice core.

A mechanical drill head from which a finished drilled ice core is pushed out. Photo: Sepp Kipfstuhl

With each drilling, a small piece of a few metres is drilled and then brought to the surface. There it is divided into even smaller pieces of half a metre to a metre, put into metal tubes and labelled. Then the ice cores are taken to the storage facility, which is also located in the trench in the ice. Quite practical, because in this way the ice sheet itself takes over the function of the freezer.

When drilling many hundreds of metres deep, it is important to make sure that the borehole remains stable. Due to the high pressure in the deep ice, there is the risk that the borehole will be compressed again over time. To counteract this, a special fluid is put into the borehole, the so-called drilling fluid. This can be a wide variety of fluids, but the important thing is that they do not freeze and have the right density. They basically replace the ice that was there before and the borehole does not deform.

For such an ambitious drilling project, many helping hands are needed. That’s why there are always a lot of people in the camp in summer. They drill day and night, because the sun shines 24 hours a day. The drilling teams are divided into several shifts, since sleep is still a must. They sleep and cook in tents or in small transportable dome-shaped huts, the so-called Igloo Satellite Cabins. These can sometimes be given amusing nicknames like “tomatoes”, as the red sleeping balls were called in the NEEM ice drilling camp on Greenland.

„Tomato migration“. Photo: Henning Thing, NEEM ice core drilling project, www.neem.ku.dk

The shower is taken with melted snow. The toilet is a deep hole in the snow covered by a small tent, which may feel a bit strange at first. If you are not completely exhausted from the long day, you can go cross-country skiing, for example. The cross-country trail here is basically endless, but you shouldn’t get lost, because you’re unlikely to find people to ask for directions.

A drilling camp on the ice. Photo: Sepp Kipfstuhl

Curious Now?

Curious Now?

If you want to learn a lot more about glaciers and ice sheets and are looking for a suitable degree programme, then the Master’s programme in Geosciences (Masterstudiengang Geowissenschaften) at Faculty 5 of the University of Bremen might be something for you. They offer lectures on glaciology (the science of snow and ice) and an excursion to an Alpine glacier.

More about how you can become a glaciologist can be found here.

This was the first part of “About Ice Cores”. Here you find number two.

Sources and Further Links

Sources and Further Links

The article series “About Ice Cores” is based on the podcast advents calendar “Eis hoch 24” (ice to the power of 24) from 2020 (in German).

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC8ZphUO3AC8Xbt4SwXd589A

The topics of this article are discussed in episode 1 (Erster Schritt/first step), episode 2 (Bohrung/drilling), episode 3 (Motivation/motivation), episode 20 & 21 (Bohrcamp/drilling camp).

Drilling

https://icecores.org/about-ice-cores

http://www.pastglobalchanges.org/download/docs/newsletter/2013-1/PAGESnews_2013_1-6-7-Steffensen.pdf

https://www.iceandclimate.nbi.ku.dk/research/drill_analysing/

0 Comments

2 Pingbacks