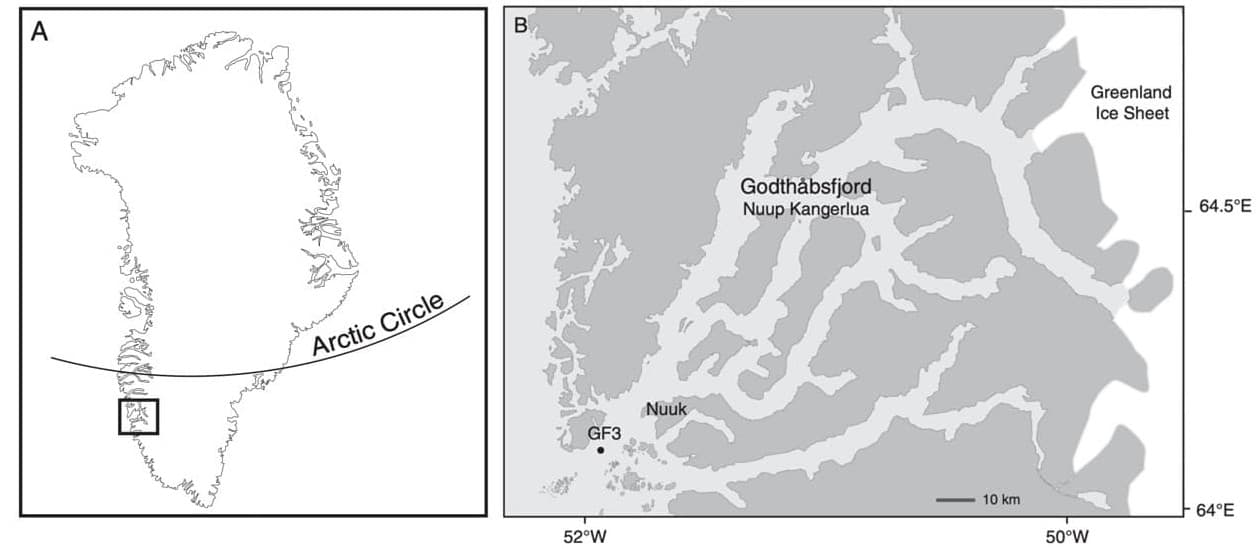

During my Bachelor’s degree I always focused on practical experience through student jobs, internships and excursions in research affiliated fields. Especially by being interested in polar regions living and working in the Arctic has always been a dream for me. Fortunately, with the University of Bremen coordinating the EU-funded FACE-IT project, an interinstitutional research project investigating the influence of climate change on Arctic fjord systems, I could use my network of scientists and docents to send my application for an internship forward to the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources in Nuuk, Greenland. I quickly was accepted and planed my own small research project investigating long term data of the zooplankton community in the fjord system Nuup Kangerlua.

Figure 1: (A) Greenland and (B) the Nuup Kangerlua system, with location of the monitoring station GF3.

2. My Internship Project

For my internship project, I was conducting research on the biodiversity and community structure of the copepod ensemble of Nuup Kangerlua. For this my supervisors provided me data from a long-term time series on zooplankton of the outer fjord. During my internship I went on several field work deployments on the fjord, where we contributed to the long-term time series. Besides three bongo net hauls (triplicates) for the zooplankton samples, the measurement of the environmental parameters was necessary. Therefore, we deployed a CTD-sensor measuring the conductivity, temperature and density of the water column. Moreover, we measured the fluorescence from which the calculation of the chlorophyll a biomass was possible. All this environmental data was later necessary to put the biomass trends of certain copepod taxa in the context of inflowing water masses, heat waves and phytoplankton blooms.

Besides fieldwork, my main task was the statistical evaluation and interpretation of the copepod data. After the zooplankton samples where send to a facility in Poland, where all taxa were identified, counted per m2 and measured, I could use a dataset consisting of 13 years of detailed information on the entire zooplankton community. After identifying the eleven most abundant copepod taxa, I started calculating the biomass for every taxon per month and put it in a plot to visualize the changes over time. We saw vast changes for every taxon and most of them showed a strong decrease in their biomass in the same time period as the others.

Figure 3: Biomass trend over 13 years of one copepod genus (example) in Nuup Kangerlua. The absolute biomass [mg C / m2] is illustrated in black, whereas the regular seasonality is illustrated in red.

From this information we discussed different theories and possible factors driving the biomass of the copepod community of Nuup Kangerlua. Higher and lower temperatures (except for the heatwave) seem to not influence the copepods, since the fluctuations are all in the tolerance range of the taxa. However, the water masses originating from different areas seemed to be a very possible driver, flushing the copepods in or out and causing different compositions of the copepod community depending on the copepod community they brought with them. Our assumption was that when the extrafjordish water masses flushed the fjord, exchanging a huge part of the fjord water, the copepod community was vastly reduced. When these water masses reached then the fjord at a later point again, we expected an inflow of many new individuals, leading to an increase in the total copepod biomass. Supporting evidence for this theory was the introduction and disappearance of some taxa correlating with the in- and outflows.

3. My Life in Greenland

Besides scientific work and education, I was also introduced to a new lifestyle in Greenland. Even though Nuuk is the biggest city in Greenland with roughly 20.000 inhabitants, it is far from being a big city in a European understanding. First of all was nature and weather a strong factor in your everyday life. This of course started with the decision of clothes depending on how far the temperature is below 0 °C, but most importantly storms could affect your plans quite drastically. With strong winds around 130 km/h, which occurred regularly, the busses stopped driving and snow reduced your vision to a few meters, making it impossible to leave the house. In addition, winds above already 40 km/h hindered planes from taking off causing delays of your travels for up to a few days. Greenlanders are used to these conditions and take it easy, whereas European newcomers have to adapt themselves first. However, these unplannable conditions also brought advantages for me. By this I had a two-day vacation in downtown Reykjavík and an extra day in Sisimiut, a small city in Greenland famous for dogsledding, all paid by the airlines.

Another huge difference was in the supermarkets, where the variety of products was quite limited compared to Germany. Instead of a huge ensemble of the same product but different tastes, sizes and brands, the supermarket just offered one or two. On some days the shelf was just empty since deliveries only arrived once a week from cargo ships. Especially fresh vegetables and fruit was a luxury, due to the relatively long transportation times from Denmark to Greenland by ship. Nevertheless, after the first few days this “culture shock” turned out to be very relaxing. Instead of many small decisions, you just took what was available and still cooked the dish the same way. However, the prices where sky rocketing. Since almost all goods had to be shipped to Greenland, everything was expensive. As an example, one meal of pasta and pesto costed roughly 7 €. Therefore, hunting and fishing in the fjord system played a bigger part in my life.

Figure 5: Old Nuuk with the statue of Hans Egede (left) and the Annaassisitta Oqaluffia (dt.: Erlöserkirche) (right)

During my time in Greenland, I participated in many traditions. One of my favorite ones is the “kaffemik”, a social gathering with hot beverages, cake and Greenlandic food that is usually performed for birthdays and other festivities. The difference to a common tea party lies in the fact that a kaffemik is throughout a whole day and guests come and go after some time to make space for the new arriving ones, since usually many people are invited. This allows you to have many interesting conversations, meet new people and have small reunions.

Figure 6: Greenlandic food is mostly based on sea food. Typical snacks are whole dried capelin (top) or dried filet parts from halibut (right) and cod (top left). Moreover, smoked salmon (center) as well as shrimps (left) and fish eggs (bottom right) are common. Fried scallops in bacon (bottom left) and shrimp salat (center right) are also common.

Another big aspect was the social life. Since I lived in a shared apartment with many other students, I had contact to students and scientists from all over the world and at different stages in their life. Moreover, via social media I could also connect with locals and participated in many activities like kayak polo, soccer, polar swimming, hiking, fishing and hunting. In general, outdoor activities are quite popular and you meet many people out in the wild while hiking, fishing or hunting.

Since I was in a (sub-) polar region during the winter, I experienced a lot of darkness. Before I left, many people could not understand my decision to spend an entire winter in darkness there, but I was more optimistic. Nevertheless, it really was dark and when the sun rose above the horizon it was already about to set again; the shortest day lasted 4 hours. However, everyone put lights on their houses and with the white snow lightening the surrounding, the darkness felt really cozy and by far less depressing than a grey German winter. Moreover, the more darkness, the higher are the chances for seeing the northern lights. Whenever there was a clear night sky, it was very likely to see them coloring the sky.

Figure 8: Northern lights above Nuuk coloring the night sky green and in special nights even a little red.

4. Conclusion

My 5-month internship at the Greenland Institute for Natural Resources in the Greenland Climate Research Center was an enrichment of my studies in many aspects.

This internship provided me with hands-on experience in a professional research environment, which included the participation in many field work deployments, the attendance of the Greenland Science Week and exchange with many more scientists from other institutions. Furthermore, I learned a lot about the statistical evaluation of data with R from an ecological perspective. Moreover, by presenting and discussing my work to other scientist from different disciplines, I understood to defend my work and argue based on references to form my own opinion. In addition to that I intensified another crucial skill for the work as a researcher: scientific writing. By going through the entire process of a research project, I prepared myself well for future assignments and my thesis.

Besides professional value the internship also allowed me to come out of my comfort zone and form my personality. By living in a foreign country with many specialties and extreme conditions, I experienced personal growth towards trust in my own abilities. Moreover, I learned to build friendships quickly with new people. However, Greenland also taught me to handle loneliness better and deal with inner conflicts or doubts.

In summary, this internship will forever be a key point of my personal and professional life with many lessons, memories and experiences.

Neueste Kommentare