During summer 2021, in the liminal space after more or less rigid lockdowns of the public art life due to Coivd19, a tremendous project on Smell had been curated in the federal state of Bremen and Bremerhaven. More than ten public locations for art & culture coordinated exhibitions and events under the title “Smell it! The Fragrance of Art” (Catalogue by Wienand 2021), including a number of outdoor stations to explore smell in our local environments, really exciting. Somehow a new mapping for hidden smells in our city space had been invented (www.smellit.eu). Marie Gronemeyer, one of our course participants and bloggers, visited the exhibition at the central museum for arts, Kunsthalle Bremen.

“To smell with the eyes: Images of Scent since the Renaissance” (12.6. – 15.8. 2021)

Let´s listen to Maries impressions:

As a regular visitor of the exhibitions of the „Kunsthalle Bremen“, I was thrilled to be able to explore their current collaborative project „Smell it“. Following the theme of „Olfactory Art“, approx. ten exhibitions around Bremen and Bremerhaven invited the visitor to explore their surroundings through the sense of smell, in a world dominated by sight.

In an online lecture, offered by the “Kunsthalle Bremen” featuring Professor Jonathan Reinarz, from the University of Birmingham (UK), this hierarchy of senses has been acknowledged since centuries. Therefore, the exhibition aimed to make us look a little harder for the smells surrounding us and to try to capture these fleeting scents, Reinarz explained. The visitor was encouraged to look further than the obvious through critical thinking. Besides highlighting smell extremes – pleasant and unpleasant alike -, the exhibition also aimed to create an awareness on smellscapes of everyday life.

According to Reinarz, the power and importance of the olfactory sense predominantly lies within its ability to tell stories. This aspect was enhanced through a story wall in the exhibition, which featured snippets of written pieces created by local students. On another note Reinarz focused on the history of smell, especially the concept of essential barbarism, which led to people trying to cover up unpleasant odours. Within the victory of sanitary motions, human scents like bodily fluids were furthermore privatized.

Similarly, the painting “Fish Stall” by Frans Snyders tries to trigger disgust, through creating visuals that evoke the smell of gutted fish. Focusing on the volatile character of scents, Snyder is able to capture the paradox of fish being a luxurious item, yet being prone to rot soon. When I looked at this painting which displayed different shades of pink, the ability of smell to change one’s perception hit me yet again. From afar, I thought this painting looked beautiful and I was soon drawn to it. When I got closer and saw the title “Slaughterhouse (Study)”, I was immediately repelled due to the smell it evoked within me. This change in perception, from a positive first impression to then feeling disgusted, made me realize the power of smell first hand.

On the other hand, Honoré Daumier´s piece “L´Odorat (Les cinq sens)” depicts a person rolling their eyes back with longing and pleasure, while sniffing on herbs and flowers. Thus emphasizing the other and more positive side of smells. Comparably to the division into pleasant and unpleasant smells, the potential of smells to in- or exclude people and therefore forming distinct groups in society, is furthermore discussed within the exhibition.

The Romans are mentioned as an historical example of smell based division, whereas smell was associated with primitive behaviour. Reinarz mentioned that, historically speaking especially non-Westerners were viewed as “smelling bad”. For instance, after the “San Francisco Plague of 1900-1904” struck the residents of Chinatown, ethnic foods were associated negatively and deemed to be smelling bad. Similarly to this case, Reinarz also mentioned a sanitary survey of a Brazilian public health campaign, that tried to find the source of a disease by following their noses to the Brazilian slums and without proper testing. Later they found out that the cause of people getting sick was in fact spoiled food, not the slums.

On a more positive note smell also has the ability to connect people, especially in terms of religious practices, where certain scents are used for purifying. Specific scents, as sandalwood (used in rituals of Buddhism) and rose water (used in rituals of Islam) are seen as an expression of devotion, due to being a luxurious product. Furthermore, it is said, that the scent leaves a trail, connecting heaven and earth. Thus, even after leaving church, the people would remain connected with one another.

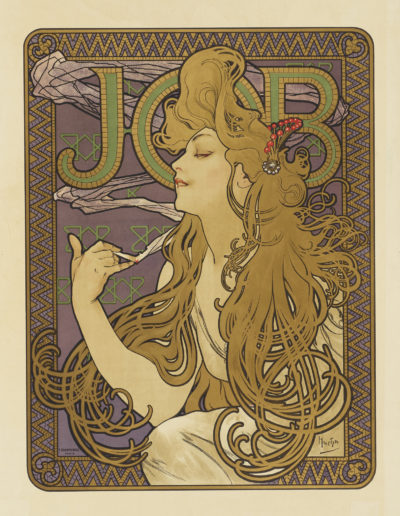

A more modern take on scents is the aspect of being a luxurious item and product for consumption at the mass market. Reinarz explains that marketing strategies for scents have three basic components. First brand awareness, through the visual art-designer. Second working with visuals like women and flowers, which invoke certain associations. And third, including artificially created scents that cannot be found in nature, like the famous Chanel No. 5. The professor claimed, that the worth of a scent is furthermore measured in how far the components have travelled. The hierarchy and display of power through smelling is once again highlighted by the fact, that the scents of the most luxurious homes are often sourced in the poorest places and under the poorest conditions.

Besides the historical art pieces, the constellation “New Cartographies of Smell Migration” by artist Oswaldo Maciá, takes a postmodern turn on the global distribution of scents in particular through their movements. While his painting marks this through global trade, winds and animal population, this effect is additionally visualized through moving scented bulbs in the exhibition hall. This constellation embodies the essence of the exhibition perfectly, in combining smells, sound and visual. The moving and buzzing of the light bulbs reminded me of honeybees collecting pollen by travelling from flower to flower. When I stepped closer, I could smell the scents that were released by the bulbs. When I closed my eyes and took a deep breath in, the scent of beet syrup, musk and warm wood, immediately summoned memories of my hikes through the woods this summer.

Another highlight was a gigantic pink walk-in nose, which even had cushions as boogers. The “breathing” sound lured curious visitors right to the entrance of this exhibition, and reminded them “to smell with the eyes”.

Inspired by this exhibition, I want to document the museums smellscapes the next time I visit. I look forward to explore new smells, like the perfume and aftershave of the other visitors, as well as the familiar smells of coffee and cookies from the museum cafe and freshly printed ink from the souvenir shop – thus forming invisible and amorphous sculptures, uniquely capturing the essence of the room for a fleeting moment.

Unfortunately most of the explicit exhibitions have already closed end of August 2021, but the multi-located event left uncountable tracks and traces of fragrance for the visitors, which they will be reminded of when crossing certain parcs, locations or museums in the near future. Many thanks to the many organizers and curators including the funders of this wonderful enterprise to enhance our sensitivity on hidden smellscapes in our cities Bremen and Bremerhaven.

References: Smell it! Geruch in der Kunst. / The Fragrance of Art. A joint project of ten museums within the federal state of Bremen. Catalogue by Wienand, 2021