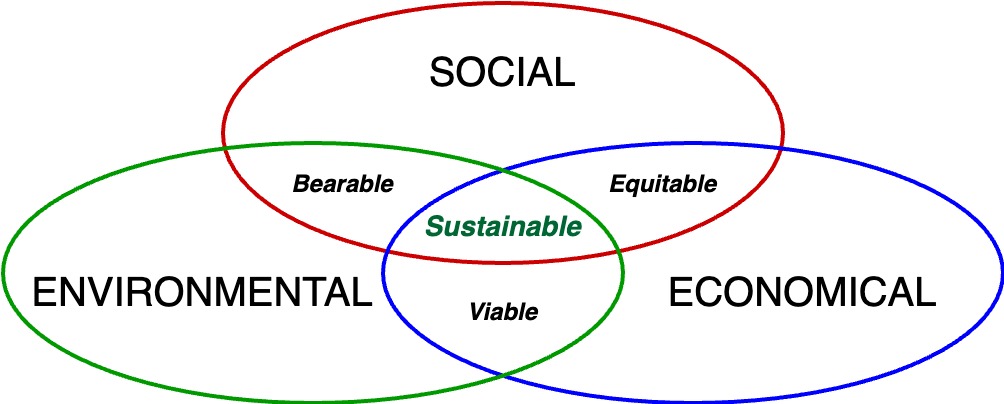

Hey everyone! Let’s talk about something that’s been on my mind for a long time now: the sustainability of our academic travels. It’s a tricky topic because it mixes economic, social, and environmental factors. I will try to break down these elements and suggest ways we can make smarter travel choices without giving up on the benefits that come with attending conferences and other academic events.

Making Smarter Choices

-

Trains Over Planes: If you can, take the train. It’s usually a greener choice.

-

Fewer Flights: Try to fly less by combining flights with trains. Also, look into carbon offset programs; many institutions offer these automatically.

-

Green Stays: Choose hotels that are known for sustainable practices; many search engines already provide this information.

-

Extend Your Visit: If you’re traveling far, why not make the most of it? Visit a local lab, give a lecture, or just explore the area. It makes your carbon “spend” go further. Maybe you can also visit the places where you change vehicles anyhow.

Managing Travels in the Group

-

We maintain a list of the top conferences and where they take place each year (approximately 10 conferences are currently on the list).

-

We prefer sending our papers to the closest top conferences.

-

If there are really no other options, PhD students are allowed to submit to a remote conference, but they can only go if a full paper is accepted.

-

When organizing the travel, we always check for flight options from Hamburg, which is much better connected than Bremen and very often has a direct connection to our destination.

-

Exceptions need to be made, for example, when serving on the organizing committee or for extended research stays (sabbaticals and internships). We discuss all exceptions in the team meetings, consider alternatives, and how to make the travels even more useful.

Wrapping Up

This question is a real evergreen and seems really hard to answer (it is hard). I typically say: aim high in quality, do not overdo it in quantity, and do not waste anything by not publishing it. I am lying sick in a hotel room in Austria and I am bored. So, I decided to explore my own citations from the last 7 years.

This question is a real evergreen and seems really hard to answer (it is hard). I typically say: aim high in quality, do not overdo it in quantity, and do not waste anything by not publishing it. I am lying sick in a hotel room in Austria and I am bored. So, I decided to explore my own citations from the last 7 years.