Silencing Stories

Patriarchal structures and sexual violence as a taboo?

“Whether experiencing sexual violence is coded as shameful, or on the contrary is recognized as involving ‘courage, heroism and bravery’ significantly affects whether, when and how it is remembered and articulated.” (Altinay and Peto 2016, p. 14)

Finding out that the topic of sexual violence during the Armenian Genocide rarely is discussed by my interviewees, the question on the reason behind it arose. During the interviews, it turned out that this issue has many different roots but one stood out the most: The stigma that comes with the experience of sexual violence. Like Altinay and Peto already nicely framed in the quote above – it is the way the issue of sexual violence during the Armenian Genocide was addressed that had a direct effect on how it is remembered now.

To understand this present situation and the memory culture that we have created, more often than not my interviewees started speaking about the past – particularly the victims. Since the contemporary witnesses are also a very important factor in memory culture and in this case very hard to find, I wanted to understand what stories my interviewees were aware of from female genocide survivors. During her answer to this Mary explained that there were actually many women who were never able to share their experience:

Mary: “So it always has me thinking about…like knowing the stories, it always has me thinking about how many stories do we not know about? And that’s that chilling moment of ‘Oh no, we know ten but there might be hundreds that we don’t know about’. Or maybe we know ten and we don’t know five? But the fact that we don’t know that five is scaring me in a way that maybe those stories were even more tragic, that these people never talked about. Ehm…And also like not hearing their voice is bothering me. Like, their stories went silent. And every story has so much more in it […]”

The fact that Mary is implying that there are actually untold stories is the first reveal to what can be recognized as the missing female voices in this issue. She is even scared by the idea that there is still something left to be told which will now never be heard since most of the contemporary witnesses are not present anymore. Since many Armenian women were sold into slavery or to Turkish men, their whole identity was deconstructed and they were forced to build a new persona that was detached from their Armenian culture (Miller 1993, p. 103). In chapter 4.2. I already mentioned that only a few hundred of those women actually were able to get out of those marriages (Derderian 2005, p. 10). Since they had to deny their Armenian identity, they were unable to tell their stories and thus were silenced forever. Without their stories from their perspective, we cannot grasp the whole issue and thus cannot correctly advocate for it. This leads to the topic in itself diminishing into the background.

Shortly after the statement of Mary, Mona intervened and argued that it is not only tragic that those stories were not heard since some women might not need “that validation to be able to move forward”. In her opinion, “someone’s coping mechanism and their way of moving forward is to never talk about it again.” A real discussion erupted between the both of them which hints at how difficult it actually is for them dealing with trauma and at the same time trying to raise awareness for the sexual violence suffered by those women, especially if those women cannot speak for themselves. It is a balancing act between respecting the privacy and personal space of the victims while at the same time giving them a platform to be heard (Attarian 2016, p. 266). The exact dispute that Mary and Mona had, is the question that I had in my mind as well. According to Lentin “survivors of a catastrophe often silence themselves or are silenced by society” (1999, p. 5). Mona acknowledged that there are women who did not want to speak about their experiences with sexual violence or chose not to speak about it but there is also the other side that Mary addressed of women who are deliberately silenced. I brought up the shame factor that was attached to sexual violence for Armenian women in chapter 4.2. as well. Even though they both did not blatantly state it before, Mary described the shame that is attached to sexual violence very openly:

Mary: “I think it’s probably part of the “My grandmother’s tattoos” the movie or the documentary when they discovered that she was in the genocide because of the tattoos she had or else she never spoke about it. So that also plays into it I think. A big portion of like ‘Hush, hush, don’t talk.’”

In the words of Altinay and Peto, when it comes to war and genocide, we would rather see a woman “who kills [herself] and [her] daughter to avoid rape” than a woman who “endure[s] or even use[s] [her] sexual labor for survival” (2016, p. 14). It was the movie which brought this issue to Mary’s mind and made her think about it more deeply which means that there is some type of existing comprehension. Consequently, the shame factor is already recognized by the interviewees and addressed through movies and books. However, it is not enough to start a larger debate in the circles that my interviewees are part of. At the same time, this shows that the existing stigma of the 20th century had a lasting effect on our way of dealing with this issue now as well. Mona ties the present and the past together and states that: “Yeah, like if you’re discussing culturally our attitude towards sexual violence towards women, then at one point or another we tie it back to ‘Of course it’s a taboo conversation because [it] happened to so many women during the genocide.’” Interestingly, there is no question about it for Mona that the way sexual violence against women during the genocide was stigmatized in public is the reason why women nowadays have to fight the same kind of stigmatization.

It is not a coincidence in this regard that we are specifically speaking about women who are silenced. The interviewees spoke of internalized power relations that played its part in the unconscious avoidance of the topic in the Armenian society. Mary was the first one speaking of a “power dynamic” which can be understood as the power that the Ottoman Turks had over the Armenian women but also as the power that men hold over women in general, in the Armenian community. Those specific power structures were used against the Armenian community:

Lara: “Yeah, it was a symbol of the place of the woman. You should not speak, you should not appear, we should not see you. You are here to please the men of the house. So yeah, not only in the Armenian society, in those Easter societies. So, I guess raping societies. There is a different sense, like there is a different meaning, maybe than in Europe. I think in Europe rape that occurs now – this is lead by sexual need or someone who has a sexual problem and raped women but maybe in the Eastern societies rape is a way to destroy your family. Because…I’m not saying that this is normal but I’m saying that in these Eastern family, especially at that time. Maybe not now, I hope not now, in Eastern family raping a woman was like dishonoring the family”

So, based on Lara’s assumption there is a difference between the meaning of rape or sexual violence in western societies and what it entails for the Armenian society. She even goes as far as describing them as “raping societies” which ultimately implies that it depends on the society structure how the sexual violence is handled afterwards. Since especially in patriarchal societies virginity and sexual virtue are highly important, survivors of rape are often shamed for it (Reid-Cunningham 2008, p. 290). What is meant by “patriarchal society” can be seen in women’s position in the Armenian society during that time. This can give us an insight on what role sexual violence plays in the memory of today’s society.

First of all, the conditions that prevailed during the 20the century were shaped by male dominance in the Armenian literary and scientific world. Mostly men were the ones documenting what happened during the Armenian Genocide and afterwards. After all, the position of a woman was defined as the family keeper not as a worker (Talalyan 2020, p. 16). Thus, female writers or researchers were rare to find. Even during my research, I noticed that although the literature that I had chosen for the part of sexual violence was mostly written by women, a large part of the literature for the Armenian Genocide in general was written by men. The women that did have the opportunity to write and share their own stories had a very hard time. Zabel Yesayan, an Armenian female writer of the 20th Century, struggled with her own female identity because of the stereotypical rules female writers were required to adhere to (Nichanian 2015, p. 32f.). Since men are responsible for the retelling of history and remembrance, they tend to avoid questioning their power position in society (Seifert 1993, p.12). Political sociologist Lentin Ronit describes this precisely when he argues that memory is split into the traditional version of history on one and the experiences of women on the other side (Lentin 1999, p. 6).

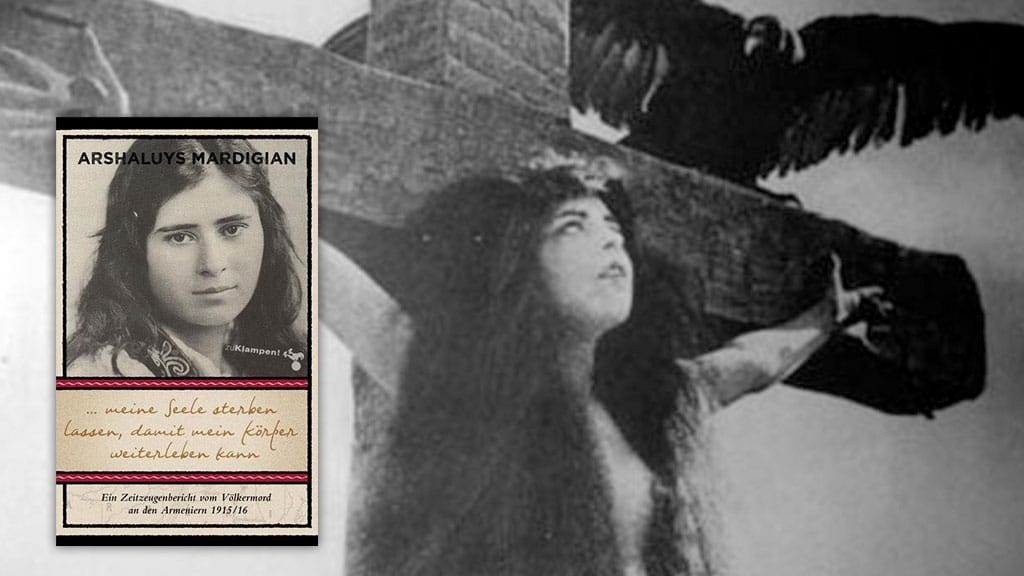

Another great example for this is the book allegedly written by Arshaluys “Aurora” Mardig(an)ian [5]. As a survivor of the Armenian Genocide, Arshaluys immigrated into the US in 1917. After an interview of her was published in the newspaper, the screenwriter and journalist Harvey Leyford Gates became interested in her and the “commercial potential she had” (Frieze 2018, p. 64). He became her legal guardian and promoted her career. Subsequently, she became a relatively famous actress starring in a Hollywood movie called “Ravished Armenia” about the genocide. For this role, however, she was not paid sufficiently (Mardigian and Hoffman 2020, p. 182f.). In 1918 Arshaluys wrote a memoir in Armenian which was published afterwards. However, the published version was not written by herself since she did not have a proficient level of English. Gates had rewritten it beforehand “using a translator” (Frieze 2018, p. 64). Since Arshaluys was not able to read it, she had no way of knowing how her story was described. This resulted in her memoir being put through multiple subjective perspectives until it ended up as a biography. Ultimately, the experiences of a woman were put through a male filter which can also be noticed when reading the book. Her many different experiences of sexual violence were only hinted at and not named as what it clearly was (Mardigian and Hoffman 2020, p. 183). Mary spoke of her as well during the interview:

Mary: I feel like she was really misunderstood. I think she came out as this crazy Hollywood star vibes which is maybe very much tied to her trauma. I don’t think that is talked about as much. It was like “She was a star!” and it’s like, okay yeah she was a star but there was a lot behind that she was masking maybe and again like she did…I don’t know if she had the platform to open up and really truly talk about who she was inside and part of me thinks, seeing the photos and the make-up she did…that makes me thinking maybe she was hiding behind all of that, like, her…this was…America was her new life and that inspired all of it.

[5] Turkish soldiers

The story and her persona are known to Mary and it was the first name that came through her mind when she was speaking about survivors. Thus, it is clear that there was attention given to a female victim that suffered from sexual violence. However, Mary also mentions that she felt like the appropriate platform was still not given to her. Even though Mardigian’s story was publicly dealt with, it was not told from her point of view. The many different versions of her name hint at the persona that was rather created for her, that she had to live up to without regard to her personally or her real story. She and her experiences as a genocide survivor and sexual violence victim were used as a way to gain mass attention similar to the stories of other victims (Boric quoted in Lentin 1999, p. 6). Even the website of the Aurora price which bases its own organizational name on her pseudonym only acknowledges her with a few sentences and nothing more (Aurora Prize 2021). It is not a female victim telling her story but rather a story told for her, constructed to abide the rules of a patriarchal society (Seifert 1993, p.13).

In addition to this, Mary and Mona addressed something that was formerly not apparent to me during my literary research. Both of them found it irritating that the cinematographic way of portraying sexual violence consisted of concluding that rape victims mostly are virgins:

Mary: “On the topic of like the movies that you mentioned I don’t…now that we talked about it, I don’t like how sexual violence is so much tied, in especially movies, to virgin women, like not…like you don’t have to be a virgin to suffer sexual violence, like that’s what you would see in the movies that it’s like a girl, axchika (engl. girl). She is not married, she doesn’t have kids, she never had sex. She experiences sexual violence but that’s not how it was. Like people who had children with their kids present, like they were raped.”

Mona: “That just goes like, culturally, what we value and what we don’t. Like that speaks to our attitude towards virgin women vs. not virgin women.”

Mona speaks of the attitude that the community has towards virgin women. Proving what Mary and Mona already assumed, there is in fact a high importance for women to be virgins in the Armenian culture. Especially the Armenian Apostolic Church has its influence on the role of women in the Armenian society and in what way they are supposed to integrate themselves into it. A woman has to be a virgin before entering the covenant of marriage. There are no exceptions made for this (Talalyan 2020, p. 20). The virginity of a woman is seen as something that needs to be protected, thus raping her is an intervention into the family relations and the construct of the Armenian society (Talalyan 2020, p. 22). Since the church is of uttermost importance to the Armenian community everywhere, there is no doubt about the fact that this social standard is still relevant today. Even though it is arguable to what extent this still persists nowadays.