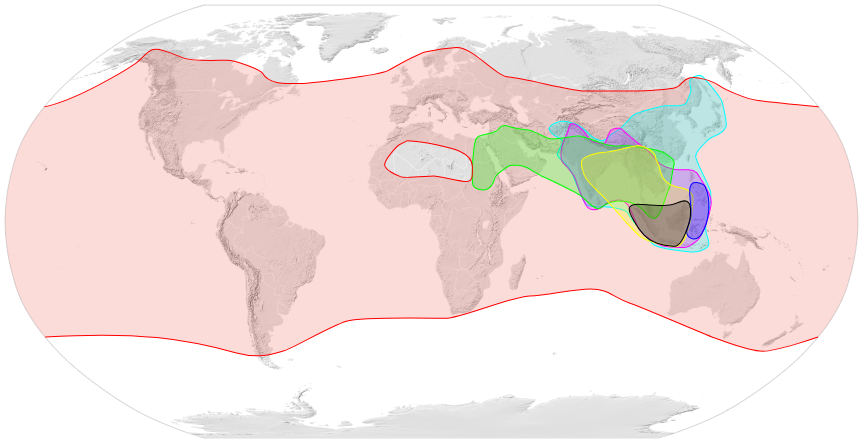

Honeybees (Apis) are spread over most of the world today. Exceptions are areas where climatic conditions prevent their survival, for example in deserts or regions where it is too cold. Seven honeybee species with 33 subspecies that can be roughly defined geographically have been identified (Ilyasov et al. 2020). Clear distribution areas are not always possible to discern. Hybridisations have occurred and continue to occur in the contact zones of subspecies and in areas where bees have been introduced by humans. All seven honeybee species originated in tropical southern Asia. Only two species have spread to temperate climate zones: The Eastern honeybee Apis cerana is native to India, Japan and large parts of Southeast Asia. The Western Honeybee Apis mellifera is native to Europe and Africa. Through colonization and the global bee trade, Apis mellifera has spread to South and North America, as well as Australia and New Zealand. On those continents, honeybees were absent before human intervention while various honey-producing stingless bees and other pollinators existed. Additionally, European honeybee subspecies were introduced in parts of Asia and Africa where they now coexist with native honeybee species.

Apis mellifera hybrids

Beekeeping in Hamburg is practiced with different Apis mellifera subspecies and their hybrid offspring. Germany was previously populated by the dark bee Apis mellifera mellifera but this sub-species has been largely replaced by different non-endemic sub-species that were introduced by beekeepers due to their supposedly superior characteristics, mostly the Austrian Apis mellifera carnica. This shift in the bee population has been intensified by the international trade of bees and queens as well as the breeding that is common in conventional beekeeping. Another factor was the arrival of the bee pest Varroa destructor in Europe in the 1980s which caused the extinction of the wild honeybee population in Germany and other European countries. Unlike its original hosts, the Eastern honeybee (Apis cerana), colonies of European sub-species of Apis mellifera die within a few years if they are not treated against Varroa mites. In a densely populated country like Germany the mite quickly infested the entire wild honeybee population. This means that only treated bee colonies survive. Non-tended bees that live in natural cavities are the immediate offspring of tended bee colonies and will die within a few years.

Apis mellifera adansonii

Beekeeping in Ngaoundéré is practiced with the African sub-species Apis mellifera adansonii. Unlike European honeybees which depend on storing large quantities of honey to survive the winters, African honeybees do not experience such long periods without food. African subspecies therefore tend to live in smaller colonies that store less honey. At the same time, African bees have to withstand extreme heat and drought. They are also exposed to predators to a greater extent than European bees. African bees deal with these challenges through absconding and migration whereby the entire colony leaves its hive in order to move to a new place (Hepburn and Radloff 1998, 148–53).

Migration is a seasonal phenomenon that takes place to escape great heat or drought or other locally specific circumstances. It can be seen as an evolutionary alternative in the context of the extreme climate and seasonal forage in Africa. Absconding, on the other hand, takes place when a colony of bees leaves the nest in response to a disturbance, such as exposure to animals, humans, fire, rain or heat. European honeybee subspecies are not able to leave their nests in the same way but only leave their hives when swarming for reproductive purposes.

African bees live in smaller colonies and collect less honey. They abscond if they encounter problems. These traits allow Apis mellifera adansonii to live with Varroa destructor mites without treatment. Beekeeping in the Adamaoua Region – as in most of sub-Saharan Africa – is based on attracting wild bee colonies. African honeybees are more defensive than European bees. They tend to attack humans over minor disturbances. For protection, Adamaouan beekeepers often use improvised protective clothing and a lot of smoke.

Apis cerana japonica

Apis cerana is a eusocial, cavity nesting and honey producing species of Apis. It is somewhat smaller than the Western Honeybee and lives in smaller colonies that produce less honey. Apis cerana are able to abscond, which means that an entire colony can leave its nest. Japanese bees are said to be extremely sensitive and abscond in the case of minor disturbances. While it is possible to keep Japanese Bees in frame hives, most beekeepers use fixed comb hives, either traditional log hives or modern Pile Box Hives. Beekeeping with the Japanese Bee is based on catching swarms – either of feral bee colonies or of the beekeeper’s colonies. In order to do so, many beekeepers use bait hives that are prepared with the Kinryohen Orchid (Cymbidium floribundum) or artificially produced attractants.

Apis cerana is the original host of the bee parasite Varroa destructor. Co-evolution has led to a balanced relationship between parasite and host. The bees have certain traits that make it possible to live with the mite. For example, the bees groom each other to remove mites from other bees. Moreover, the mites only reproduce in the drone brood of Apis cerana and not in drone and worker brood as with Apis mellifera. Unlike European sub-species of Apis mellifera, Japanese bees do not need to be treated against Varroa destructor. The Japanese Bee also displays particular defensive behavior against a local predator, the giant hornet. When attacked by a hornet, Apis cerana japonica form clusters around the attacker and produce heat by flexing their wing muscles. The heat and CO2 inside these ‚bee balls‘ kill the hornet. Western bees do not show this defensive behavior and therefore cannot live without the help of humans in Japan.

In their relationship with humans, Japanese bees are very docile. They rarely attack or sting humans. Japanese beekeepers hardly use smoke and often work without protective gear.

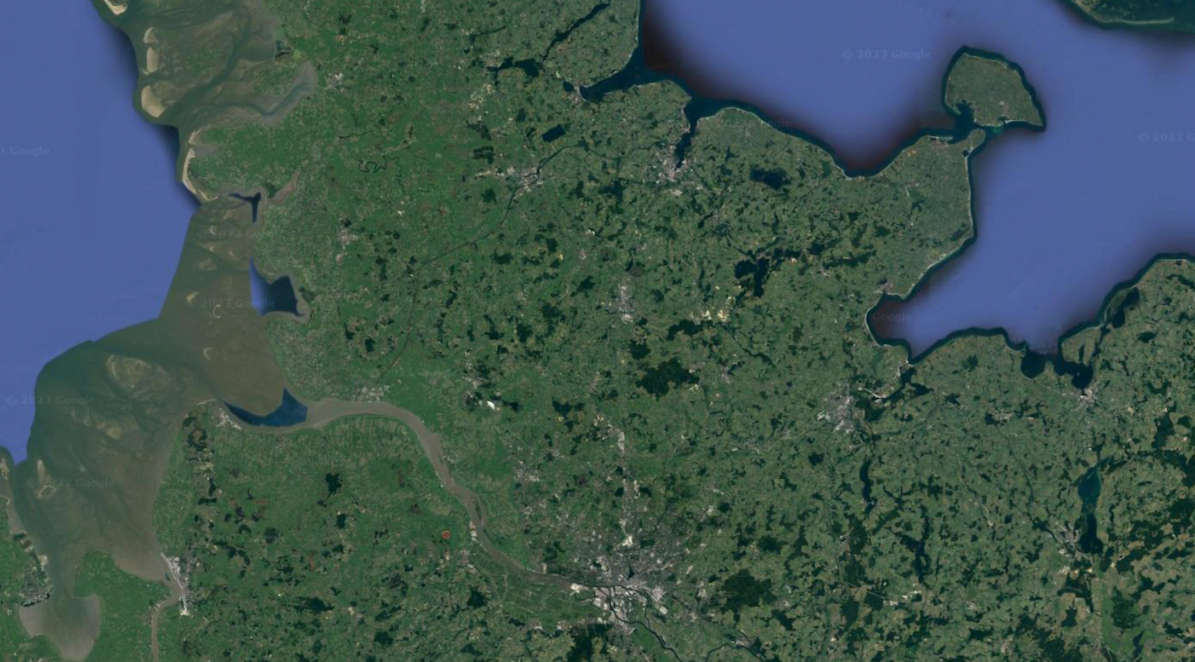

Hamburg, Germany

After a steady decline since WW2, the number of beekeepers in Germany has been rising again. Urban beekeeping has increased disproportionately. Situated in the north of Germany, Hamburg is the second largest city in Germany city with approximately 2 million inhabitants. In 2023 the city’s 1697 registered beekeepers kept a total of 7664 bee colonies, which equals an average of 10 colonies per square kilometer. This is extremely high compared to rural areas, where the density is typically around 3 colonies per square kilometer.

While the proportion of female beekeepers is rising, especially in cities, beekeeping is still a largely male domain. Nationally, around 20% of the beekeepers are female. This percentage rises to around 30% in Hamburg. My research suggests that urban beekeepers are a privileged group in terms of education and employment but at the same time, the young urban hipster beekeeper is only a cliché (Gruber 2021). While over 80% of the beekeepers in Hamburg have been practicing their hobby for less than 10 years, their median age is 55 years. The average age of my research participants in Hamburg when they started their beekeeping was 47.

I conducted autoethnographic research amongst a small group of beekeepers whose practices oscillated between alternative and more conventional methods. Alternative beekeeping practice emerged from the perception that (conventionally kept) bees do not thrive. Therefore, alternative beekeepers try to make living conditions as natural as possible for their bees, intervening as little as possible. What exactly this means varies from person to person but there are some common practices which include beekeeping with natural comb, allowing reproductive swarming and the natural mating of young queens at the apiary.

The two approaches, convenetional and alternative, are based on different ideas about the nature of the honeybee and its relationship with humans. Conventional beekeeping treats the honeybee as a domesticated animal that cannot survive (any longer) without the support of humans. Alternative beekeeping sees the honeybee as a wild animal that can (and should) only be manipulated by humans to a limited extent (Moore and Kosut 2013; Niedersteiner 2020). In practice, the two fields cannot be sharply distinguished, as many beekeepers flexibly combine alternative and conventional approaches. Therefore, not all beekeeping methods can be clearly assigned to one of the two schools as follows.

Conventional beekeepers usually try to maximize the bees’ nectar intake and to make honey harvesting as simple and efficient as possible. For such a practice, magazine hives with movable frames are particularly suitable. The mobile frames make it possible to extract honey efficiently with the help of a honey extractor. In order to stimulate colony growth and maximize nectar input, conventional beekeepers increase the volume of their hives during the flowering season. Another element of conventional beekeeping is preventing the reproductive swarming of colonies as this is seen as a loss of bees that diminishes honey production. In order to prevent the colonies from swarming, conventional beekeepers enlarge their hives by adding additional supers. Others remove queen cells from their hives or clip the queen’s wings in order to prevent her from flying away with a swarm.

naFor alternative beekeepers, the production of honey is often not a priority. Some of them do not extract any honey at all. Others harvest small amounts of honey for their own personal use. Those alternative beekeepers for whom honey production is important adhere to certain principles of beekeeping. Mobile frame hives are common amongst alternative beekeepers because they do not want to do without the advantages, but they prefer hives that replicate ’natural‘ cavities: with undivided brood nests and relatively large frames that allow the bees to store brood, honey and pollen on the same comb. Alternative beekeepers who adhere to stricter standards use fixed comb hives, in which there is less scope for human intervention. Examples are log hives or skeps as known from traditional beekeeping as well as newer types such as Warrée or Bienenkiste.

Alternative beekeepers who adhere to stricter standards use fixed comb hives in which there is less scope for human intervention. Examples are log hives or skeps as known from traditional beekeeping as well as newer types such as Warrée or Bienenkiste. The video below depicts three honeybee colonies in my allotment garden in Hamburg Diebsteich and how they are entangled with other species, matter and the wider cityscape. Each colony lives in a different type of fixed or semi-fixed comb hive: a Bienenkiste; a hive inspired by Japanese pile box hives and a log hive made from a hollow beech tree.

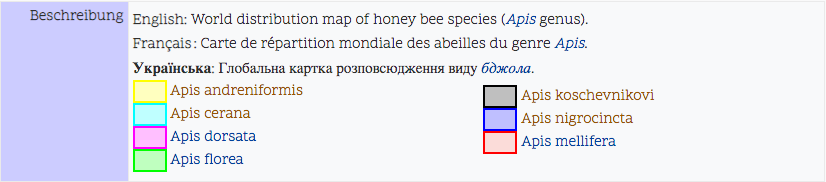

Ngaoundéré, Cameroon

Beekeeping in log hives and baskets has been practiced in Cameroon for at least 150 years and the trade in honey and wax goes back at least to colonial times. By far the most important area of honey production in Cameroon is the Adamaoua Region. It is rich in flowering plants and has a long dry season that allows many colonies to be established and large stocks of honey to be produced. 93% of the honey in Cameroon is produced in Adamaoua. Its 12,000 beekeepers manage an average of 45 hives, each producing an average of 10.5 liters of honey. Beekeepers earn an annual income of FCFA 207,000 (€315), which represents 43% of their total household income (Ingram and Njikeu 2011; Ingram 2014).

I have been conducting ethnographic research in collaboration with bee biologist Mazi Sanda of the University of Ngaoundéré since 2015. Ngaoundéré is the political and administrative center of the Adamaoua Region and the seat of the regional government. The city is an important hub for the honey trade in Cameroon and beyond. It is located on the main road that connects the north and the densely populated south of the country. The Trans-Cameroon Railway provides a direct connection to the national capital, of Yaoundé and the port city of Douala. Wholesalers based in Ngaoundéré buy honey in villages throughout the Adamaoua Region. They process and pack the honey which is shipped by train and truck to the cities in the south and to the neighboring countries. Additional honey is sold locally, or to travelers who buy honey from one of the many street vendors at bus terminals and train stations.

Honey is produced primarily in the countless villages and homesteads throughout the Adamaoua Region. The further away from the cities and main roads, the fewer people live there and the more intact the ecosystem is but even in the villages, agricultural activities and the production of firewood and charcoal are leading to deforestation. Trees that are sources of nectar and nesting sites for feral bee colonies are increasingly rare in the vicinity of human settlements.

Beekeeping in the Adamaoua Region is based on attracting swarms of feral bee colonies to move into hives that the beekeepers place in forests and the savannah landscape. Human-made hives put up by the beekeepers compete with natural cavities such as hollow trees and holes in the ground. Beekeepers try to make their hives more attractive with a lure made out of propolis and other ingredients. This kind of beekeeping depends on a large number of natural swarms or of a large feral bee population in the respective area.

Most beekeepers in the Adamaoua Region work with ‚traditional‘ hives made entirely from locally available natural materials. Cylindrical in form, they have a length of up to 120 cm and a diameter of 35-45 cm at their base. The hives consist of an inner basket like structure that is woven from strips of palm frond. A second layer consisting of plant leaves gives protection from sunlight, wind and rain. The hive’s outer layer is made out of long grasses that are tied around the framework with liana. At the base, the hive’s opening is closed with a lid made out of palm fibers. This closure, which has a small central hole as the bees’ flight hole, can be removed for harvesting honey. The production of these hives requires great craftsmanship and artistic skill. The hives represent deep embodied knowledge of the materials and the natural environment which is the focus of an ethnographic film produced in 2015.

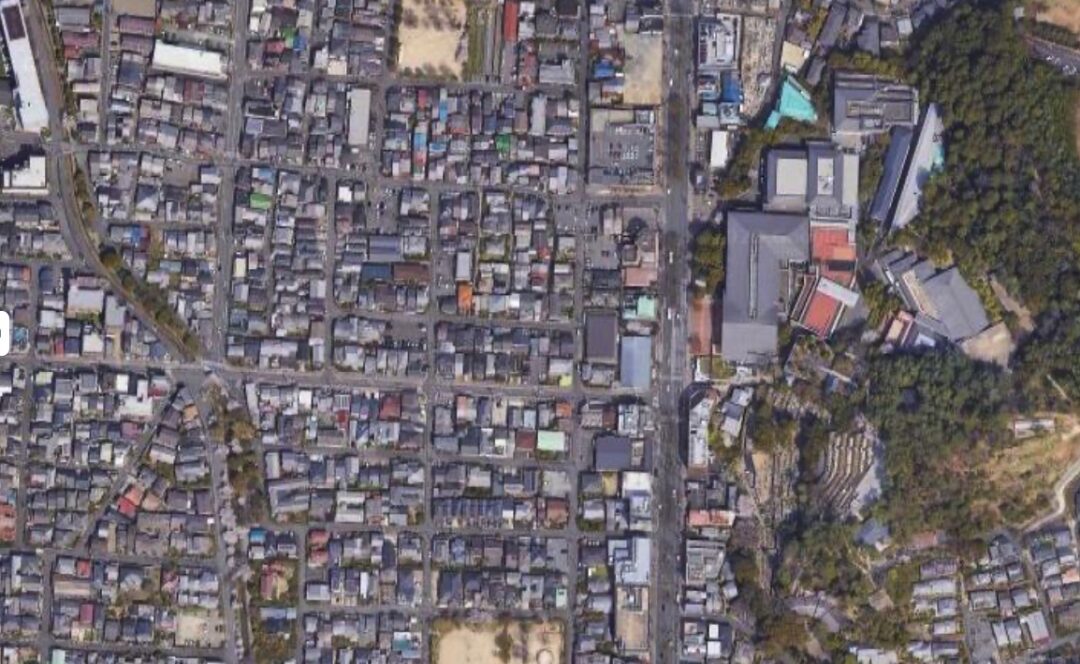

Kyoto, Japan

Beekeeping in Japan is practiced with two distinct bee species. Firstly, the native Apis cerana japonica and secondly the imported Apis mellifera. While beekeeping with the Japanese Bee goes back for centuries, the Western Honeybee was introduced to Japan in the late 19th century in an effort to modernize api-culture and agriculture. Today, Apis cerana japonica and Apis mellifera co-exist on most Japanese islands. However, there are no Japanese Bees on Hokkaido and Okinawa and no Western bees on Tsushima Island. Japanese beekeepers with an interest in pollination and honey production usually keep Western Honeybees, while traditional beekeepers and new hobbyist beekeepers prefer keeping Japanese Honeybees. I conducted research exclusively with Japanese Honeybees and their human counterparts in Kyoto and the surrounding area in 2018.

The recent increase in hobby beekeeping in Japan is closely linked to the popularization of the Pile Box Hive – a fixed comb, multi-story hive consisting of square wooden supers. Adding supers makes it possible to enlarge the breeding chamber and facilitate the honey harvesting. The Pile Box Hive existed for some time alongside log hives and box hives before well-known Japanese beekeeper Ikumi Shiga started to promote bee keeping with the Pile Box Hive by providing elaborate online documentation including a construction manual and a precise description of how to keep bees with it. This made it possible to start beekeeping with no previous beekeeping experience and relatively few costs. At the same time, he started manufacturing and selling hives and beekeeping equipment.

Ikumi Shiga’s activities were brought to a new level by his son Yuichi Shiga who started a website called ‚Mitsubachi Q and A‘ (Honeybee Q and A), which allowed beekeepers to ask questions related to beekeeping and get peer-feedback from other users. Later Yuichi Shiga and his wife Mayu started their own social media channels dedicated to the Pile Box Hive. Today they have over 200,000 subscribers while 11,000 beekeepers were registered with the Japanese government in 2022.

Together with my Japanese colleague Rika Shinkai of the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, I conducted ethnographic research on urban beekeeping in Kyoto. We encountered a very active urban beekeeping scene that included rooftop beekeeping of the ‚Kyoto Mitsubashi Garden Promotion Project‘ on the roof of Kyoto City Nakagyo-Ward office, the activities of the ‚Kyoto University of Art and Design Beekeeping Club‘ and Hitomi Ohkubo’s honey delicatessen ‚Au Bon Miel‘.

View references.